A two-day roundtable takes a big eraser to identity lines

“I’m looking for the mestizo eye, the mestizo subjunctive, the mestizo soul,” says author John Phillip Santos as we wander through Retratos: 2,000 Years of Latin-American Portraiture at the San Antonio Museum of Art. He pauses before “Retrato de un Matrimonio,” by 19th-century painter Hermenegildo Bustos. Husband and wife have light brown eyes and dark brown hair, but where she is decidedly European in appearance, with pale skin and delicate features, his ancestry seems more indigenous: broad cheekbones and a chiseled nose. The work reflects “mestizo compassion,” suggests Santos.

“Compassion” is not a concept frequently associated with “mestizo,” a word that has spent much of its 600-odd-year history wielded as either a derogatory description for the children of European and Native American unions, or as a battle cry in the Chicano identity movement.

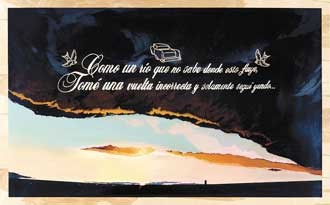

| A Southwestern landscape by Ricky Armendariz, top, is on view as part of his one-man show at Blue Star Contemporary Art Center through March 13. |

Circa 1523, in a creation myth that is equal parts fact and mystery, La Malinche — the mysterious Mexican Pocahontas — and Hernán Cortés founded the mestizo race with their first-born son, Martin Cortés, who would return to Spain with his father to further serve the aims of colonial-era Europe. Mexican and Chicano ambivalence over the legacy of La Malinche illustrates the problem with fully embracing mestizo identity: It means embracing the white conqueror father as well as the subjugated, but re-ascendant, indigenous mother. While La Malinche is celebrated by some as the mother of the Mexican people, she is alternatively known as La Chingada — the fucked.

In a sense, embracing the Virgen de Guadalupe — a mestiza Virgin Mary — is embracing an alternative mestizo birth, a virgin who conceived a new race without being defiled by the “other.”

But for Santos and an increasing number of Latino scholars, mestizo is the face of an optimistic future. “We are all mestizo. Our heritage is global. It quarrels with borders; it quarrels with demarcations,” he says, echoing his mentor, Virgilio Elizondo, the San Antonio priest who wrote The Future is Mestizo in 1986. Elizondo and Santos are two members of the organizing committee for the “Revealing Retratos,” Taller Popular, a private, two-day conference that will be held this weekend at SAMA and Trinity University, and includes such participants as Henry Estrada of the Smithsonian Latino Center, author and artist Ito Romo, Sandra Cisneros, and Graciela Sanchez of the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center. A public conference will follow April 22 at SAMA.

Santos and his co-organizers want to explore the development and portrayal of mestizaje through the images in the exhibit as a way of catalyzing a longterm conversation about identity, politics, and cultures. “I think people are fairly well stuck in an early 20th-century mindset on mestizaje, and haven’t connected it to multiracialism and multiculturalism,” says Trinity professor Arturo Madrid, another of the conference’s leaders. “This was brought home to me many years ago, when I was visiting Israel and raising issues having to do with the Palestinians. My host said the fact is that multicultural societies are just hanging on by their teeth in this world.”

Santos and Madrid believe that embracing a broad concept of mestizaje can be an antidote to the nationalist identities that often underlie human conflicts. “It’s a challenge to supremacies, apocalyptic narratives, `and` triumphalism,” says Santos, “something akin to our evolution beyond slavery.”

As we walk through the exhibit, Santos points out a 1757 portrait, titled “Mujer Indigena,” which reveals the complicated history of mestizaje in Mexico. An attractive 16-year-old mestiza girl wears an opulent and mesmerizing combination of European and indigenous clothing. Her father is a provincial governor, but despite his exalted position and the family’s apparent wealth, she is on her way to a convent built specifically for indigenous women.

Yet, there are hints that the relationship between Europeans and Native Americans might have gone differently. Near the beginning of the show, a digital print holds place of pride, even though the original did not travel to San Antonio. It is a portrait from 1599 of three black men, “Los Mulatos de Esmeraldas” (“The Mulattos of Esmeraldas”), holding spears and extensively pierced with gold jewelry. The men are zambos, a ruling elite descended from shipwrecked African slaves who intermarried with local natives in the future Ecuador. Their portrait was commissioned when they attended the accession of Philip III in Quito.

| The enigmatic mid-19th-century portrait, “Woman from Bahía,” of a richly dressed Afro-Brazilian woman, is one of several paintings in Retratos that raises intriguing questions about race and cultural standing in Colonial and post-Colonial Latin America. |

Madrid mentions “Los Mulatos” as the “most stunning” example of mestizaje in early Latin America, but he also points out the portrait of Simón Bolívar, the “liberator” of South America. “He’s represented historically in all kinds of ways,” observes Madrid, “but the one we have there really shows a mestizo face on Bolívar — whether it was true or not.”

But for all their interest in the historical development of mestizo identity, Santos and Madrid are particularly concerned with its contemporary manifestations, which is where the SAMA exhibit, for all its strengths, stops at the U.S. border. `Madrid says he and Santos have begun discussing a Part II, that would include contemporary Chicano artists, among others.`

“Latin America is no longer ‘there,’” agrees scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, who will give a keynote address Friday evening. “It’s here in the U.S.” North America is a young Garden of Eden, in which a new variation of mestizaje is declaring itself to those who are still worrying about whether to teach English-only or bilingual education. The title of a 1996 Cinco Puntos publication sums up the current state of affairs: The Late Great Mexican Border. In essays about drug trafficking, children growing up in actual dumps, and California’s notorious Proposition 187, which sought to deny social services to undocumented immigrants, the authors make it clear that the ties that bind El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, Brownsville and Matamoros, and every other concentration of humanity on either side of the national boundaries are far stronger and deeper than a fence or a river.

“El Paso is not really Texas, and Juárez is not really Mexico,” says painter and UTSA professor Ricky Armendariz. “Things go there and they become something else.”

Armendariz’ one-man show at Blue Star Contemporary Art Center, “Confessions of a Singin’ Vaquero,” explores the Southwestern landscape as a repository and wellspring of meaning and identity. The artist’s dramatic large-scale sunsets and sunrises are covered with dichos and lyric fragments, which Armendariz says he employs in part to “lift up” the humble landscape genre.

But the images can also be read as the promised limitlessness of the once border-free West hemmed in by cultural expectations (or lack thereof) — an illustration of how confines imposed by others, by racism and classism, can be transmuted into self-imprisoning points of pride. But Armendariz’ dichos are in Spanglish, the evolving language of mestizo Tejas. “By combining the two languages,” he says, “it has more meaning.” And more possibilities.

Armendariz says he arrived at this point in his work by returning to the observational methods that he learned in art school. Several years ago, living in Boulder, Colorado, he was making work that dealt with “brown and white.” But “after 9-11, those issues seemed exhausted,” he says, touching on Santos and Madrid’s desire to transcend reductive notions of identity.

A native of El Paso, Armendariz says his life is mestizo. “Freddie Fender was my hero growing up. He was doing it. He was singing in English and Spanish, making sense of my life.”

“It’s easy to romanticize multiculturalism,” cautions Santos. “But how we get to live with it is another question. That’s why it’s important to understand that mestizaje is a process and not a panacea.”

Ybarra-Frausto adds that, from his perspective, the goal is “the insertion of the local into the global.”

“In the arts, everybody talk about ‘post,’ he says. “And yet, a lot of people are just beginning to define their identity.” Our society hasn’t adequately addressed such issues as educational and wage inequality, he reminds us, but globalizing the concept of mestizaje provides new opportunities for viewing and challenging old problems.

“It’s poignant from a movement perspective,” says Santos. “At the very moment these `marginalized` voices are first coming to consciousness, that the bottom should drop out and reveal a much more complicated reality.”

Part of the complicated reality Santos is alluding to is the breathtaking advancement of genetic science, which now can offer people a glimpse of their ancestors’ origins — and the results don’t always mesh with family history and personal identity. Santos pauses before a triptych of DNA analyses prints, “Carter, Anna, y Daryl,” by Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. “How we find ourselves culturally is almost incidental to who we are,” he muses, and then brings up Code 46, the 2003 film by Michael Winterbottom. He calls the film’s sci-fi future a mestizo dystopia, because the inhabitants are forced, through DNA monitoring, to be mestizo — a solution that would be no better than denying or suppressing mestizo identity.

“Can we become a mestizo republic that ascribes to no faith but embraces all faiths?” asks Santos. “It’s going to take something like an abolitionist movement.” •

By Elaine Wolff