As soon as the Current has a free moment, it will pen a letter to New York Times etymologist William Safire: Was the phrase “no news is good news” coined before the word “bureaucracy”?

Because if you’re a King William resident or former Blue Star Art Silos tenant waiting for word on the ongoing asbestos testing at the Big Tex site, no news simply means you’re not on the arbitrary mailing list. At this stage of the game, the Environmental Protection Agency considers it the property owner’s job to keep the public informed of the site’s status, while the landlord claims the EPA hasn’t kept them in the loop.

In the meantime, what the public doesn’t know is that folks at the EPA and the Government Accountability Office agree that former silo renters — mostly grassroots galleries and cash-strapped artists who occasionally crashed at their studios — should get screened for asbestos exposure. The highest concentration of asbestos found so far at the site is around Building 10, which housed the “popper” that heated vermiculite ore from Superfund site Libby, Montana. Building 10 borders Blue Star road, which runs through the center of the long, narrow property, and a large open area adjacent to the silos.

An October 2007 EPA Site Update, sent to an unknown number of individuals and organizations, reported that this spring’s sampling of nearby Brackenridge High School and a vacant King William lot found a “very low” risk of exposure to asbestos fibers at both locations. The final sentence reminded readers that based on partial sampling in July and August 2006, “there is human health risk on the site as well as on the hike and bike trail.” According to the EPA and TCEQ, this information was shared with Big Tex owner James Lifshutz last fall, but no regulations require the government to contact former residents at this stage of the evaluation.

Big Tex, which is slated for a multi-million-dollar mixed-use redevelopment by Lifshutz, is a former W.R. Grace processing facility that handled 124,000 tons of asbestos-contaminated vermiculite from Libby from 1961 to 1989. Of 271 known sites nationwide that processed Libby vermiculite, 19 so far have been designated for cleanup by the EPA. Big Tex is on track to be number 20, but the path has not been smooth. Since 2005, when community members first became aware of Big Tex’s history and began pressuring local government leaders to intervene, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the EPA have taken turns collecting soil samples, passing the buck, and wrassling with Lifshutz.

Within the past month, Lifshutz withdrew his application to TCEQ’s Voluntary Cleanup Program, choosing instead to work with the EPA, which can seek reimbursement for the cost of remediating the site from the original polluters. Based on those worrisome samples taken last summer, the EPA plans to conduct more thorough testing this winter before making final recommendations for cleaning up the site.

“`A ‘popper’ is` the worst kind of facility as far as getting asbestos into the air,” commented John Stephenson, author of a new GAO report that directs the EPA to reassess the Libby sites it has evaluated. Libby’s amphibole asbestos is tiny and much more mobile compared to the asbestos that the EPA’s old regulation standards were based on, and the majority of those former processing sites were examined using outdated information and technology. But even if you use the latest testing methods — as the EPA is doing in San Antonio — all the sampling and screening will only get you so far, because the EPA still needs to develop a meaningful way to measure the risk of exposure to Libby asbestos. Deadline for new toxicology levels: 2010.

Amid this scientific uncertainty, who will notify the silos’ former occupants that they should keep in touch with the EPA, too? Until the site was fenced off this spring, numerous artists and galleries, including the original Fl!ght and i2i locations, occupied the small spaces for monthly rates ranging from $230-$315, and the rough-and-ready site became a First Friday hotspot, with parties and performances in the gravel lot. While tenants were specifically forbidden to live in the silos, it was no secret that for many artists, the studios served a dual purpose.

“I have stayed several nights at the silo,” emailed one former tenant on condition of anonymity, “and even called it my home for some time.”

Another wrote that she stayed all night at the site during First Fridays, napping for a while in the wee hours before driving back to Leakey.

Fl!ght Gallery Director Justin Parr, who rented two silos over the course of four years, described the property management as hands-off. Lifshutz provided a bathroom and trash cans, and while the rent was “all bills paid,” the heating and A/C units ran on timers. “In summer it was an oven and in winter it was a freezer,” he wrote — not exactly homey conditions, unless it’s the only haven you have.

“I guess I had one for about a year, and for two months of that time I didn’t have an apartment so I was sleeping in my silo,” emailed another artist, who added that he suffered from a scratchy throat after he’d been sleeping at the site for about a month.

“Absolutely,” said GAO’s Stephenson when asked if former tenants should consider getting screened for asbestos exposure, but according to “the letter of the law,” he adds, the EPA isn’t required to notify residents of potential risks until the site is officially in remediation. EPA On-Scene Coordinator Eric Delgado declined to guess how quickly that might happen.

While several of the artists interviewed for this story recalled receiving notice of the initial 2006 tests, only one of them was familiar with the EPA’s most-recent update. The EPA’s Jon Rinehart says it’s Lifshutz’s job to call another public meeting to share the progress to date, but adds that he’d like to see regular public meetings and more community outreach about Big Tex’s status. It’s worth noting, as Stephenson says, that “There are bad practices, good practices, and best practices.” In case the EPA and San Antonio are looking for models, the GAO report, available at gao.gov, offers examples of all three, including site cleanups in which residents were contacted by phone as well as with flyers, newspaper announcements, and mail.

Given that we won’t really know how much exposure to Libby asbestos is dangerous for a few more years, perhaps caution is in order, but the EPA’s Delgado is optimistic about the site’s prospects.

“`Big Tex` could be a model for urban-core redevelopment,” says Delgado, who is similarly

sunny about the City’s adjacent Eagleland hike-and-bike trail along the San Antonio River `see “Bridge to nowhere,” online at Sacurrent.com`.

This is welcome news to LeAnne Berreth, Big Tex property manager for Lifshutz. “That’s good to know,” says Berreth, who added that the EPA hasn’t contacted them directly about the latest developments. “I thought it was kind of bizarre that the only notice we got was a flyer,” she said of the October 2007 Site Update.

Lifshutz was out of the country when called for comment, but Berreth says he is ready to move ahead with Big Tex’s development as soon as the site is remediated. Plans include several residential buildings, she said, some commercial space, and would potentially incorporate some of the silos — presumably at post-asbestos rates. •

________________________________________________

Bridge to nowhere

Bridge to nowhere

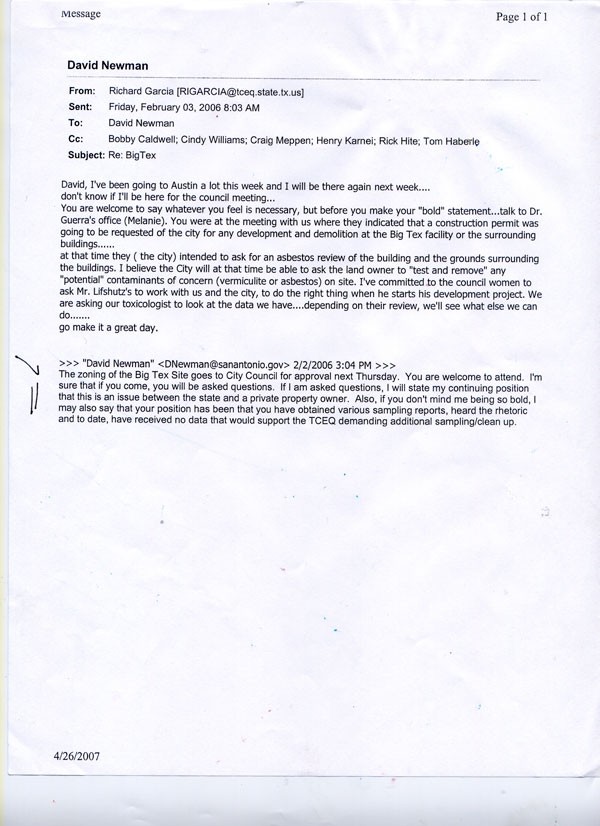

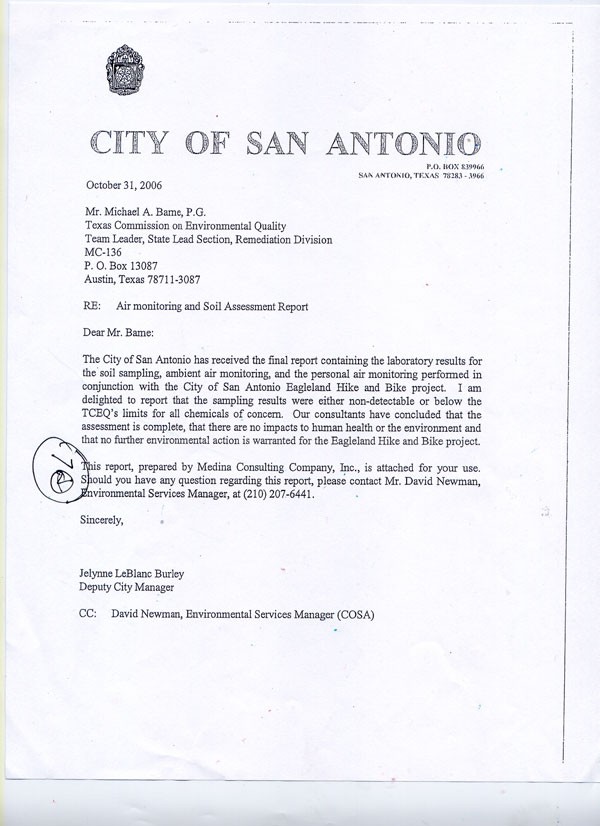

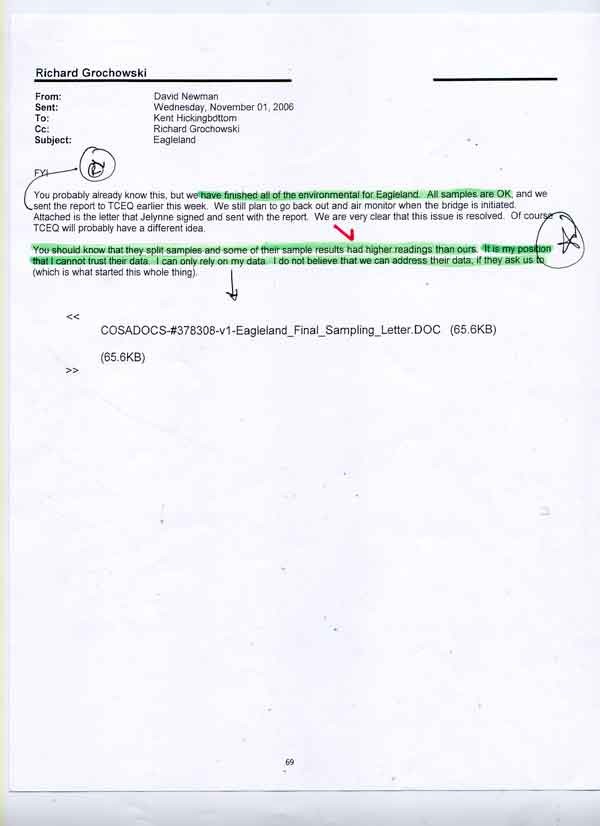

While the City, under the regulation-savvy guidance of Environmental Services Manager David Newman, plowed ahead with Eagleland Hike and Bike trail construction over the objections of the EPA and TCEQ (“We could not stop them,” says TCEQ’s Michael Bame) — the Eagleland bridge, which would link the future Big Tex redevelopment to King William, is on hold pending a construction plan that doesn’t involve traipsing through asbestosos-contaminated Big Tex.

A worst-case scenario would involve waiting until the Big Tex site remediation is complete (a date uncertain no one is willing to prognosticate), says the City’s Richard Grochowski, but working with the EPA, he hopes to make a decision within the next two weeks. In the meantime, says virtually everyone interviewed for this story, from Newman to the EPA, feel free to hike and bike in peace. Although an October 2007 EPA report mailed to an unknown number of residents and organizations concluded that “the Activity Based Sampling indicates that there is human health risk on the site as well as on the hike and bike trail,” EPA On-Scene Coordinator Eric Delgado says any danger to the public has passed.

“`The Eagleland Hike and Bike Trail` is basically not a health threat because `the City` capped over where there was a threat,” says Delgado. “Essentially what they did is performed a remediation action by putting that concrete there.”

(Looking for a primer on slashing through annoying government red tape? See a few select Newman communiques below).

________________________________________________

The Current’s Big Tex Chronicles

Available online at sacurrent.com,

or by calling (210) 227-0044

“Big Tex: the unbelievably tortured story of reforming a Libby site,” June 27, 2007

“Big Tex moving day,” March 28, 2007

“Home soil,” August 23, 2006

“Doing asbestos they can,” June 7, 2006

“Developing environmental oversight,” May 3, 2006

“Big Tex lives to fight another day,” February 15, 2006

“Nixing Big Tex,” May 12, 2005