When galvanizing figures rise from nothing to change the course of American history, they leave behind lasting legacies.

In many cases, controversial legacies.

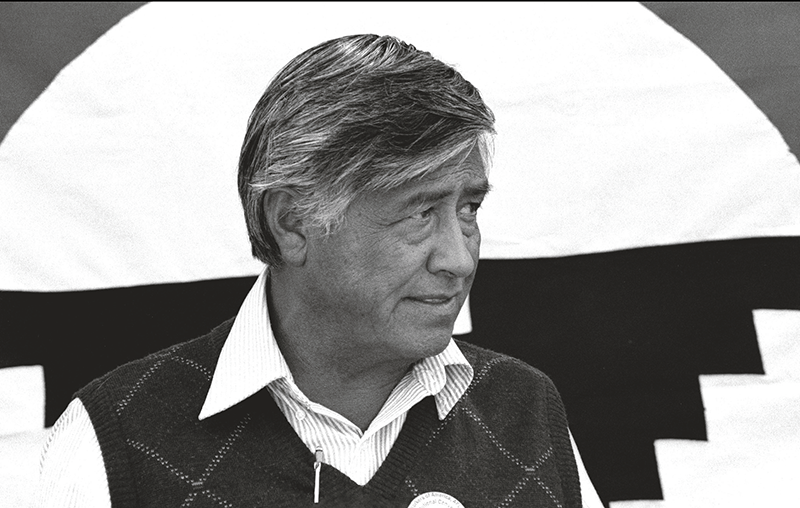

Civil rights leader César Chávez is no exception.

Chávez, co-founder of the United Farm Workers union in 1962, was remembered across the country yesterday, his birthday anniversary.

President Obama designated March 31 as national César Chávez Day, though it's not a federally-recognized holiday.

Without Chavez and Dolores Huerta, his leading partner and a renowned activist in her own right, farm workers in California and across the country would have been victim to low wages and slave-like working conditions far longer.

Chavez is remembered for striking, boycotting and fasting — nearly dying in the process — yet his controversial view on immigration is a thorny issue typically left out of his historical narrative.

Tea Party talking heads and anti-immigrant advocates have adopted racial slurs used by Chávez — like "wetback" — against strike-breaking immigrants in the 1970s as propaganda against immigration reform while leftist activists tend to ignore this side of the iconic activist altogether.

But determining whether Chávez was virulently anti-immigrant isn't easy when placed across a historical backdrop that has changed dramatically since the UFW first began organizing in the fields.

And determining its impact back then, as well as what it means today, tends to depend on whom you ask.

Miriam Pawel, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of The Crusades of Cesar Chavez, said understanding Chávez's immigration views is complicated.

"He certainly had implemented strong policies against immigrants at various points in time and against illegal immigration, particularly," Pawel told the San Antonio Current.

In 1974, Chávez spearheaded the controversial "Illegals Campaign." The strategy was simple: UFW members were to report undocumented immigrants to the now-defunct Immigration and Naturalization Service, known as the INS.

Manuel Chávez, the leader's cousin, simultaneously ran "wet lines" in Arizona with hundreds of UFW members patrolling the border to stop undocumented immigrants from crossing the Rio Grande to work as scabs during a strike.

"That was a pretty violent setup and it was financed by the UFW. So all of that is part of his record on immigration, but stems from his feelings of difficulty of winning over immigrants," Pawel said.

Chávez felt immigrants only had an interest in money, which they sent to their families in Mexico, which worked against the union's efforts to improve wages and working conditions of American pickers, she added.

For her book, Pawel said she spent hours listening to taped meetings between Chávez and other UFW leaders during which illegal immigration, Chavez's use of racial slurs and campaigns against immigrants were hotly debated.

But talk to Marc Grossman, spokesman for the Cesar Chávez Foundation, a San Antonio nonprofit advocacy group, and a different picture emerges.

"There are two separate and distinct issues and some people confuse them, unintentionally or deliberately," Grossman, who served as Chávez's speech writer for two decades, told the San Antonio Current.

In many cases, the UFW and Chávez promoted and protected the rights of undocumented immigrants working on the farms, but on the other hand, in the 1960s and 1970s during labor strikes, companies would hire undocumented immigrants as scabs in attempts to break union strikes.

But what's wrong is to use a broad brush in labeling him as anti-immigrant.

"There are those out there who say he was against undocumented immigrants or immigrants in general and that's just absurd, and the union's history belies that misinterpretation," Grossman said. "Sometimes they'll dig up 40- or 50-year-old news clips where he uses the word 'illegal' or 'wetbacks' to describe illegal immigrants. That's just how people talked back then."

Grossman acknowledged that his boss did go through a linguistic transformation, eventually dropping the slurs.

He also pointed to Chávez's support of President Ronald Reagan's 1986 amnesty for nearly three million undocumented immigrants; the UFW's 1973 opposition to a federal law requiring employers to verify immigration status of employees; and efforts to end the Bracero Program, a legal guest worker scheme that legally imported Mexican farm workers from the 1940s until it ended in the 1960s.

"He was someone who truly understood and predicted the mushrooming social and economic political influence of Latinos ... He predicted what is happening today and what we're seeing across the country," he said.

Grossman was critical of Pawel's reporting on Chávez's immigration views, but she stands by her work and is quick to list off Chávez's myriad of accomplishments improving the lot of U.S. farm workers.

"Denying that things happened is to deny people the opportunity to learn from the history," she said.

Such lessons are more important than ever now, particularly as millions of undocumented immigrants are poised to obtain legal status through President Obama's orders — pending the outcome of a legal challenge by his detractors.

Farm worker rights also continue to strike at the heart of activist movements.

Giev Kashkooli, the UFW's political and legislative director, said pickers still face atrocious work conditions, all for the lowest wages.

Improving work conditions and pay are important, yet, in keeping in line with their founder's prediction of Hispanic influence on American society, the UFW's most pressing current issue is immigration reform.

Kashkooli said 95 percent of present-day members are immigrants.

Just how crucial is Obama's legalization program to the UFW and how influential is the organization? Its current leader, Arturo Rodriguez, sat with Obama on Air Force One to review the document with Obama before the president unveiled it in November.

If it eventually goes through, it would mean legal status for a staggering 250,000 union members.

"Earlier that week, dozens of farm workers from around the country had brought a Thanksgiving meal to D.C. so Americans could understand what it takes to harvest the food," Kashkooli said.

If all of America's undocumented farm workers were deported, grocery stores across the country would struggle to fill shelves and the price of vegetables and fruits would likely skyrocket.

"It's very personal for today's farm workers and this has been true for well over 15 years when we began intensively engaging in trying to change laws," Kashkooli said.

Were he alive today, Chávez would likely do what he always did best: organize strikes and boycotts and use the power of the people to force social justice.

So he may have taken to his grave that little-discussed anti-immigrant side. Perhaps he'd want to take all that back – who knows.

But nobody's perfect. And, no matter what, no one could question the tremendous impact he had in putting Latino civil rights on the national consciousness.

That is his legacy.

CESAR CHAVEZ: LITTLE-KNOWN FACTS

One of his 31 grandchildren, Sam Sanchez, is a pro-golfer.

n 2011, the U.S. Navy named a cargo ship the USNS Cesar Chavez, which delivers supplies to ships at sea, including ammunition, food, repair parts, stores and fuel.

Before eighth grade, Chávez changed schools a whopping 38 times. That's because he grew up in a migrant farm worker family.

He was a vegetarian.

Chavez joined Synanon, a drug rehab and religious group deemed by its critics as a cult.