| Gown Town: 232 of the area’s best and brightest beautiful young ladies competed for Nationals Inc.’s Miss Pre-teen, Junior Teen and Teen titles. |

I add that it probably has to do with warmth on this chilly Friday afternoon in late November. It’s a calm moment of absurd polarity during the frantic registration for Nationals Inc.’s San Antonio Pageant at the El Tropicana Hotel Riverwalk downtown. The walls are lined with mothers wielding curling irons and straighteners like fencing swords. They parry the kinks, riposte with hairspray, as their pre-teen and teenage daughters tap their toes, impatient for their the preliminary photography session. The line to the registration table stretches out the door of the Santa Fe Room. The girls eddy and intersect as they rush from sign-in to the private interview, back and forth to the dressing rooms two or three times to pose for the Miss Photogenic photo shoots.

For 99 percent of these girls this is their first pageant, so there’s none of the vain cattiness you’d expect; only confusion, whining from the girls, and fumbling shoe-swapping from the mothers who sit on the sidelines with grocery bags of clothing changes. These aren’t your stereotypical pageant moms, either; no obsessive-compulsion, no vicarious-experience robbing or win-or-else attitudes. They’re just exhausted.

A month ago, more than 400 girls received letters inviting them to compete in the pageant. They were nominated anonymously by teachers, youth-group advisors, and other community leaders. Double from the previous year, 232 girls made it past the first interview. They then had a month to raise sponsorship to cover the $495 entry fee and to defray the costs of all the preparations: the casual and formal wear, the makeup, and, of course, the shoes.

Between grilling meat and tailing her daughter, Diana Gonzales is so tired she’s forgotten what day it is. She went to bed at 3:30 a.m. the night before and was up again at 6:30 a.m. to start delivering the 100 $6 plates of barbeque her family sold to raise the entry fee. After the pageant, she’ll drive more plates around, then be back at 9:30 a.m. for the pageant rehearsal at San Antonio College’s McAllister Theatre. Her 19-year-old, Marisela Urrabas, is stunning, with a wide, sultry smile and eyes like the wings of tired butterflies. She aspires to be a model.

“Are you going to put us in the newspaper?” Marisela, Contestant #180, asks shyly.

Diana corrects her, “No, he’s going to put the information in the newspaper.”

It’s then that I realize the significance of my presence. Even if these girls don’t place in the pageant, a media mention is almost as good. I wander around nervously. I don’t belong here, a single adult male who can’t help but stare.

A few weeks back, the Current received a press release from a contestant named Jessica Ann Green, in the hope that if we picked up the story it would encourage local businesses to sponsor her. A Google search later, I was perplexed; a teenage Miss San Antonio had already been crowned in January. Her name is Amber Newman, and she’s a 16-year-old homecoming queen with blond hair and a garish smile who attends New Braunfels High School.

I called Nationals Inc., the Miss Teen San Antonio organization. It turns out there are two competitions: theirs and Miss San Antonio Teen USA, a subsidiary of the Miss Universe pageant.

Miss San Antonio Teen USA is the more prestigious: organized locally by Ché White of Diverse Dreams, it was honored this year by the state legislature for providing its contestants “with the opportunity to gain poise, confidence, and life lessons that will benefit them for years to come” and “to further their education by earning scholarship money.”

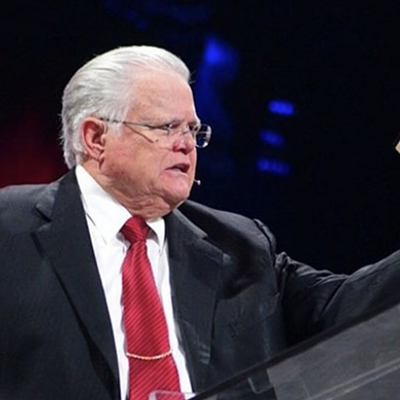

| Kari Langbein’s finest hour, receiving the Miss Teen San Antonio tiara. |

Nationals Inc. is more corporate, sending a team from the national office across the country to coordinate 77 events. As opposed to the Miss USA system, Nationals’ is more a beginners’ pageant that doesn’t include a swimwear round, and therefore draws a wider selection of girls — all shapes, all sizes — because it’s designed primarily as a confidence-building community exercise with a focus on “personality.”

“With the USA pageant, because it has a swimwear competition, if you don’t have the right body, you’re not getting up on stage,” says Nationals staff member Elizabeth Jameson, herself a former Miss Phenix City, Alabama.

The most sensible approach seemed to be to compare the two pageants and its two winners to give you, the reader, the chance to decide which better represents San Antonio.

“Amanda will be very excited to speak with you,” White told me by email, and later we talked in depth about the direction the story would take. We booked a photographer to stand-by for a shoot.

When her mother called and told me, “Amanda is very busy this week, and we will pass on this interview,” I became

distraught. I didn’t understand how someone who would be representing the city at the Miss Texas USA pageant at the end of the month couldn’t make time for an interview. I called up the ladder, imploring the Miss Texas USA organizers, the Crystal Group, to sweet-talk Amanda’s mother on my behalf. I emailed Ché again to find an alternate route: I could interview some of her friends, her teachers, and her mom could provide me with a colorful breakdown of a day-in-the-life schedule. No response.

So far, all I could say was what I found on the internet: the Diverse Dreams page describes Amanda as 5’8”, green-eyed with dark-blond hair. She’s interested in poetry and involved in activities like Youth Life and the Key Club. When one user on the Unofficial Miss Texas USA Messageboard at Voy.com predicted Newman would win Miss Texas Teen (“She looks awesome has lost 15 pounds `sic`.”), the other gossipers weren’t as sweet:

“Really! I would like to see her go back to her natural hair color, the blonde she has now makes her appear brittle and damaged. Not to mention her eyebrows are almost black.”

And:

“Her on stage interview was awful ... really bad. Unless that has changed ... top 15 no further.”

Many would argue that what I did next crossed the line, and in retrospect I concede they are probably right. In my defense: a journalist can’t kill a story when a source refuses to talk for the same reason the police don’t negotiate with hostage-takers. I called the high school advisor who helped her apply to San Diego State University.

“She’s just a lovely girl. Polite, kind, just a really good heart,” Dorothy Crews said. “She’s a very personable young lady. I would say she’s well-liked by everybody.”

Crews offered to pull Amanda out of class for an interview, but when I called back Crews said Amanda’s mother didn’t want her speaking with me.

Calling her school upset her mother and the pageant organizers. A slew of increasingly confrontational emails flew back and forth, ultimately resulting in Linda Warrimer at the Crystal Group writing: “The executive directors of the Miss Texas Teen USA pageant have decided to decline an interview with your publication. Nor will the San Antonio Teen USA titleholder be available for interview. Quite honestly, we found your attitude and your manner of doing business to be offensive … Please accept this decision as final.”

I’m sitting in the eighth row watching the pre-teen rehearsal with four junior-teen contestants, each in Saturday-morning slob-wear, except for hundreds-of-dollars worth of open-toed high-heels: Contestant #97, Anyssa Camarillo, the knowledgeable one; Contestant #106, Nichole Chavez, the funny one; Contestant #100, Artecia Nichols, the nervous one; and Contestant #107, Dejon Kidd, the relaxed one. None have been in a pageant before. They’re talking about how embarassing it all is, and the adorablenesses of the Miss Pre-teen contestants. One girl tells how a relative once bought off a judge to win a pageant; the others speculate the whole competition is a money-making scam. They object to the fact that many contestants come from outside Bexar County.

“I was talking to one of the top makeup artists in the pageant industry yesterday,” I say, “and she said the decisions are usually made during the interviews.”

The girls suddenly look glum, and begin comparing how they answered the question “If you could be any animal ...”

“I said a white tiger,” Artecia says.

“I said a butterfly,” Nichole says.

“They only live eight days,” Dejon says.

I follow them backstage where they’re led single-file through the hallways, heels clacking, attempting not to collide with the other lines of girls. Soon they’re on stage practicing the routine, and Nichole misses her cue, then suddenly stumbles forward as if pushed from behind. On the way back, as they pass the table of skyscraper trophies, Nichole steps out of line, jabs a finger in my direction and says, “I told you I was going to mess up!”

Back in our seats, Artecia’s mother wanders over to tell me to please write about her daughter. Artecia rolls her eyes. Then Devon’s mother beckons her daughter, who ignores her. She shuffles down the aisle and eyes me suspiciously.

Joseph Holloway, the SAC stagehand and one of the few males who will be allowed backstage during the pageant, summarizes my uncomfortability best.

“I’m trying to watch to see how it will work tonight,” he says, sitting on the sidelines. “But I’ve got to remember to keep looking away so it doesn’t seem like I’m ogling them. I don’t want to be the creepy guy.”

The 1000-seat theater is sold out. I’m in the second row next to the judges, and beside me our transgendered photographer Antonia Padilla sighs when she wishes she could fit into a junior-teen’s thin red gown. Padilla fell in love with pageants watching Miss America 1965 on a vacuum-tube television. She’s worked before with the other pageant, Miss San Antonio USA.

The pageant’s a tedious affair, like a drawn-out graduation ceremony at an overpopulated high school. The curtains close (Holloway’s work), and open on each line of girls, first in casual wear, and one-by-one they step forward and twirl, while the announcer reads their interests. Too often it’s “shopping.”

“Princess Heidi Lopez,” is announced, and Antonia says she might change her name to that.

“Oh yeah?” I answer, then show her the spelling in the program: P-R-I-N-Z-E-Z-Z.

In evening-wear, they answer questions, like “Who inspires you?” and “What’s your most valuable experience?” Whenever Jesus is mentioned, the applause thunders. Whenever a girl explains how one of her military parents has been deployed, an old voice man behind me intones, “Amen.” When Contestant #7, Amanda Carson, says her role model is Condoleeza Rice, a tenseness seizes the auditorium.

I point out junior-teen Contestant #82, Taylor Obermiller, a skinny-legged Jean Grey-look-a-like I noticed the day before. “She’s going to be a model,” I tell Antonia, “She certainly looks unhappy enough.”

“You’re so bad,” Antonia says.

I regret saying that when Taylor’s explains her most valuable experience. While the others described cheerleading competitions and karate championships, she recounted a story about helping Katrina evacuees at Lackland Airforce Base.

After they announce the top 10 in each category, the theater empties. I rush out into the hallway to catch the girls I know. Not one succeeded to the finals. Nichole is bearing a bouquet of flowers and a frown. “They bribed the judges,” she says and adds, “I didn’t know you needed to be an airhead to get chosen.” Artecia is deadpan. I ask her how she feels, and she answers, “It was a waste of time and money.” Dejon just shrugs.

It’s not my place to shake them and tell them they’re wrong. For all their charm and candor earlier in the day, during the real deal, under the lights, facing the microphone, each answered limply. That’s why they didn’t win. But they didn’t lose, either.

Here’s how I see it: for all the corporate-ness of the pageant (I calculate Nationals Inc. collected more than $125,000, not counting expenses), it was truly an impressive phenomenon of community support. The girls came in all sizes, shapes, ethnicities, and economic backgrounds; and behind each of them a host of small businesses and loving families and friends putting their money where there hearts are, and sitting patiently through the dinner hour for the opportunity to whoop with pride.

It was a celebration of San Antonio girlhood: First, the pre-teens in their knobby-kneed eagerness; the junior teens, in their various stages of bloom, feet and hands and necks growing faster than the rest of their frames; the teens, proud and arch-backed in their blooming womanhood. The heavy with the thin, the brace-faced with the button-nosed, goth-inspired Katrina Stevens with her big black boots, nursing student Jennifer Rumpf with her X-ray prop, Jasmine Miller with her snap-shut cell phone, the twins Chloe and Cailee Cullen, the cheerleader, the basketball star, the first female president, and so forth — it wasn’t about picking the perfect girl, but recognizing each for their individuality as San Antonio’s daughters.

The auditorium empties to a third by the time the winners are announced by “Ray” in sports-arena style: Miss Pre-Teen, Allison Nova; Miss Junior Teen, Tennessee Nathanson; and Miss Teen, Kari Langbein — all three from different ethnic backgrounds.

Like Amanda, Kari’s blond, 16, and from out of town, but the point of this story is that all girls are unique, and the first difference is that her mother lets me talk to her.

This was Kari’s seventh pageant, and she’s been in numerous pig shows, leading her 600-pound York pig, Pretty Girl.

“She was very dignified, very confident, very polite, and she had a very strong personality as far as what she wanted and her goals,” says teen-level judge Sandra Luna, a women’s health specialist.

What Kari told the judges: her goal is to get a bachelor’s in animal science, and a master’s in swine reproduction.

“After everything was done, on the way home I crashed,” she tells me the next day over the phone. “But while we were doing it the adrenaline was so there, I really wasn’t exhausted until I got in the truck.”

I think that must’ve been the case for all of them, their mothers and me.