|

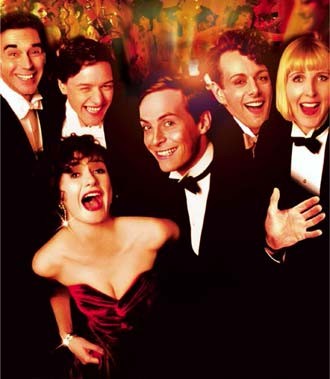

'Bright Young Things' is a timeless tale of self-deception and dissolution When Adam Symes (Moore) returns to England from a sojourn on the continent, he is detained at customs in Dover. Without even reading it, an agent confiscates the manuscript of the traveler's novel, called Bright Young Things. "If we can't stamp out literature in this country," he explains, "we can at least stop its being brought in from outside." Evelyn Waugh's novel Vile Bodies, on which Stephen Fry, in his directorial debut, based Bright Young Things, is the kind of foreign import that mental hygienists in this country might wish to embargo. Like some noxious microbe, Waugh's bilious account of avarice, intemperance, and insouciance among the high and mighty might, if left to spread, induce an epidemic of cynicism. If you look too closely at someone above you, all you might see is a pair of dirty feet. One of the scenes in the film is set in a tatterdemalion stately home that Waugh names Doubting Hall; pronounced with a certain British accent, the place proclaims universal skepticism. What we see in the flamboyant opening sequence of Bright Young Things, accompanied by jazz with a feral bongo beat, is a lavish, naughty costume ball. The dim young things who are the guests spend the movie - and their lives - flitting from one outrageous party to another. These privileged children of the ruling class are the idle rich, except when they run out of funds. Adam's insolvency jeopardizes his engagement to Nina Blount (Mortimer), a beautiful narcissist who is practical enough to warn him: "It's all very well to look down on money, but a girl's got to look out for herself these days." To pay his champagne bills and keep Nina from marrying a cad named Ginger (Tennant), Adam takes on the job of "Mr. Chatterbox," a gossip columnist specializing in mongering scandalous behavior within high society. The position becomes vacant when his predecessor, a blue blood named Simon (McAvoy), can no longer function as a traitor to his class. Torn between his desperate need to get invited to glamorous parties and his assignment to expose them, Simon takes his own pathetic life. Bright Young Things is filled with vibrant, dotty characters who could be called Dickensian if they were not in fact Wavian; among Waugh's inspired creations are Adam's fellow residents at a London hotel that has seen better times but no better characters than the melancholy deposed King of Anatolia (Callow) and a perpetually drunken major (Broadbent) who manages to win a fortune at the race track. A cameo appearance by Peter O'Toole as batty Colonel Blount resolves Adam's financial woes, until he notices that the generous check the colonel writes him is signed "Charlie Chaplin." Though Waugh published his novel in 1930, Fry concludes during World War II and with an ending sentimental enough to make the famously caustic author suffer posthumous apoplexy. Yet Fry does not attempt to update the story to the 21st century. He does not have to: The bodies might have changed, but they are as vile today as they were in Waugh's prime. Consider odious Lord Monomark (Aykroyd), a Canadian who has made himself master of a British publishing empire. It is he who hires and fires successive versions of Mr. Chatterbox depending on how many papers their columns sell. It does not matter that Adam invents stories as long as they are popular. For a contemporary foreigner who became the mogul of a media conglomerate, look no farther than Australian-born Rupert Murdoch, whose News Corporation was built on tabloid scandal sheets. Its subsidiary, Fox News, has made an art and a fortune out of stalking celebrities and redefining news as frivolous infotainment. Does Martha Stewart deserve more scrutiny than increased mercury emissions? It is tempting for Americans, viewing these snooty, silly Brits, to be grateful that castes do not exist on this side of the Atlantic. Of course, they do, though ascertaining status here is more complicated than merely consulting the social registry. George W. Bush was once a bright young thing, a legacy admission to Yale who, by his own account, majored in fun and used family connections to stay out of harm's way during the Vietnam War. Then the prodigal son found faith, and the only party that he now attends is Republican. At one of many extravagant parties thrown throughout Bright Young Things, an American evangelist named Mrs. Melrose Ape hectors the merrymakers. "The lives you lead aren't real lives," she announces. Yet, as portrayed by Stockard Channing, Mrs. Ape is a sanctimonious prig and no more real than anyone else in the movie. "Human kind / Cannot bear very much reality," wrote T. S. Eliot. That is why we have Britney Spears, Donald Trump, and Jimmy Swaggart, and why Stephen Fry sweetens Evelyn Waugh's wormwood. •

|

Tags:

KEEP SA CURRENT!

Since 1986, the SA Current has served as the free, independent voice of San Antonio, and we want to keep it that way.

Becoming an SA Current Supporter for as little as $5 a month allows us to continue offering readers access to our coverage of local news, food, nightlife, events, and culture with no paywalls.

Scroll to read more Movie Reviews & News articles

Newsletters

Join SA Current Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.